It’s been a while since I visited my favorite ponds in Delaware where I have spent many hours photographing. Carlos Martinez Rivera, herpetologist and frog conservationist with the Philadelphia Zoo, wanted to see Barking Treefrogs, so I was inspired to return at the end of May. These ponds fill with water in the fall and dry out completely most summers. Such seasonal ponds are called vernal pools and are known locally on the Delmarva Peninsula as Delmarva Bays.

Barking Treefrogs come down out of the trees in May and June to mate. When a male finds a female he climbs on her back and holds on tight. This nuptial embrace is called amplexus. He will stay with her until she lays eggs in the pond while he fertilizes them.

Most males do not find mates until they reach the pond. Note the difference in color between this frog and those in the previous photo. When they enter the water (perhaps due to temperature?) they change to a duller, greenish-brown hue.

The advertisement call that male barking treefrogs broadcast from the pond is “toonk, toonk, etc.” When they are in the trees they bark.

Another one of the ten species of frogs breeding in this pool is Cope’s Gray Treefrog. This one is puffed up and ready to call.

Cope’s Gray Treefrog calls with a fast, high pitched, unmusical trill.

If it wasn’t for the slower, lower-pitched, more musical call of the Eastern Gray Treefrog, it wouldn’t be possible to tell them apart from Cope’s Gray Treefrog in the field. Eastern Gray Treefrogs are tetraploid, meaning they have four sets of chromosomes instead of two like Cope’s Gray Treefrog or most other animals. Apparently they evolved from Cope’s Gray Treefrog. This type of evolution from diploid to tetraploid is more common in plants.

Knock two pebbles together and you can imitate the call of the Northern Cricket Frog. Males often call from floating leaves. This tiny member of the treefrog family lacks the expanded toe pads that allow other treefrogs to scale trees.

Danger lurks in the dark waters. Bullfrogs, the largest of our frogs, may make a meal of any of the above frogs.

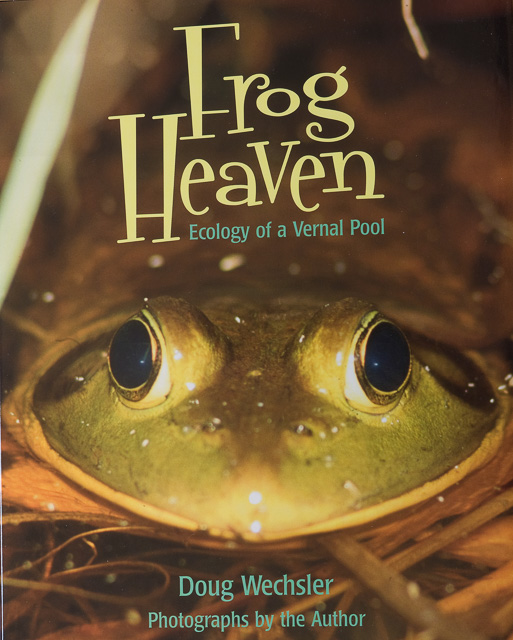

The best book about vernal pools

I love these ponds so much, I wrote a whole book about them. Frog Heaven: Ecology of a Vernal Pool follows a pond from the time it fills in the fall until it dries out in the summer. Vernal pools are critical to amphibians as well as many aquatic invertebrates, ironically because they dry up for part of the year. This keeps fish, major predators, out of the ponds. Find out more about Frog Heaven here.