What a great place for birds! It was great to be back in Buenaventura Reserve. Following up on my post from last year, here are a few more birds from Jocotoco Foundation’s. Buenaventura Reserve in the southern foothills of the Ecuadorian Andes.

Three species of toucans appear frequently around Umbrellabird Lodge what is it*****. The most vocal is the Chestnut-mandibled Toucan with its incessant yelping.

Chestnut-mandibled Toucan, Buenaventura Reserve

The Choco Toucan seems like a smaller version of the Chestnut-mandibled, but it croaks instead of yelps.

Choco Toucan, Buenaventura Ecological Reserve

The Pale-billed Aracari also commonly shows up near Umbrellabird Lodge. This one found what appears to be the egg of a chachalaca.

Pale-billed Aracari, Buenaventura Ecological Reserve

Bronze-winged Parrots pass overhead frequently, but once in a while they stop to forage in nearby trees.

Bronze-winged Parrots, Buenaventura Reserve

Plumbeous kites nest in a tree near the lodge. I have seen them take hummingbirds. But, during this visit, I watched them return to their perch with a cicada six times.

Plumbeous Kite preening, Buenaventura Reserve

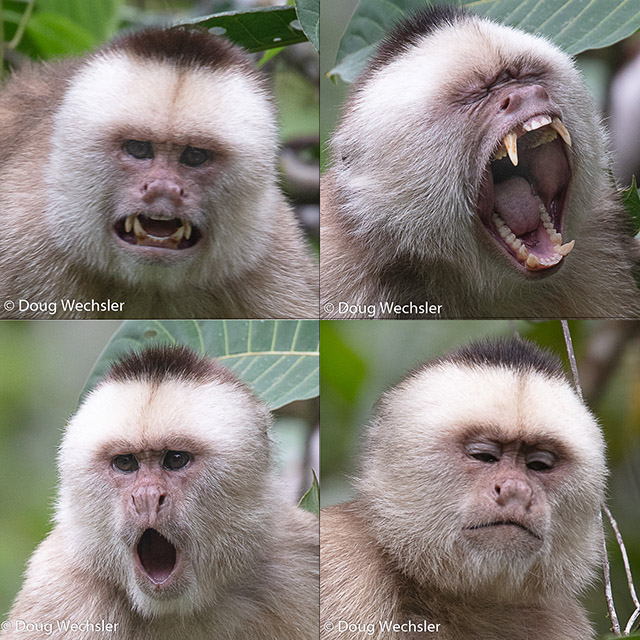

Since Debbie was in Cuenca studying Spanish, I spent a lot of time with the single males at the lek (communal male display grounds).

Usually the White-bearded Manakin maintains a well-groomed face…

White-bearded Manakin, Buenaventura Reserve

…but when displaying at the lek, it extends its white beard. Then it launches itself, zipping back and forth between two vertical saplings, snapping its wings in the air.

White-bearded Manakin, Buenaventura Reserve

The lek of the Long-wattled Umbrellabird is more spread out than that of the manakin’s. Usually only one male is visible from a single vantage point in the lek, but the foghorn calls of several males are audible throughout the lek. A male can quickly double the length of its wattle. Here it is partially extended.

Long-wattled Umbrellabird, Buenaventura Reserve

Buenaventura Reserve was established in 2001 primarily to protect the El Oro Parakeet, which was discovered by Robert Ridgely, Paul Greenfield, and Rosanne Rowlett in 1980.

El Oro Parakeet, Buenaventura Reserve

In 2006, Jocotoco Foundation initiated a major nest box program for the El Oro Parakeet. This has significantly increased the population. However, the total population of the species remains below 1,000. The decline is primarily due to deforestation, which has reduced the total area of forest in the region to 5% of the original cover. Natural nest cavities are also rare since much of the forest is young. The foundation is working to create a corridor across private and public land to protect the parakeet.

El Oro Parakeet, Buenaventura Reserve

In addition to the breeding pair, there are usually several helpers at the nest. Most of these are close relatives. Up to 13 birds have been seen entering a box.

El Oro Parakeets, Buenaventura Reserve

The helpers rarely participate in the breeding. That is left to the single mated pair.

El Oro Parakeet, Buenaventura Reserve

The Jocotoco Foundation monitors productivity of the parakeets nesting in boxes.

Leovigildo Cabrera climbs to monitor nest box

A nestling is removed from the box while an ant nest is evicted.

Nestling El Oro Parakeet

I regret that I had to leave out another 334 species, but I will close with a shot of the forest.

Secondary forest, Buenaventura Reserve